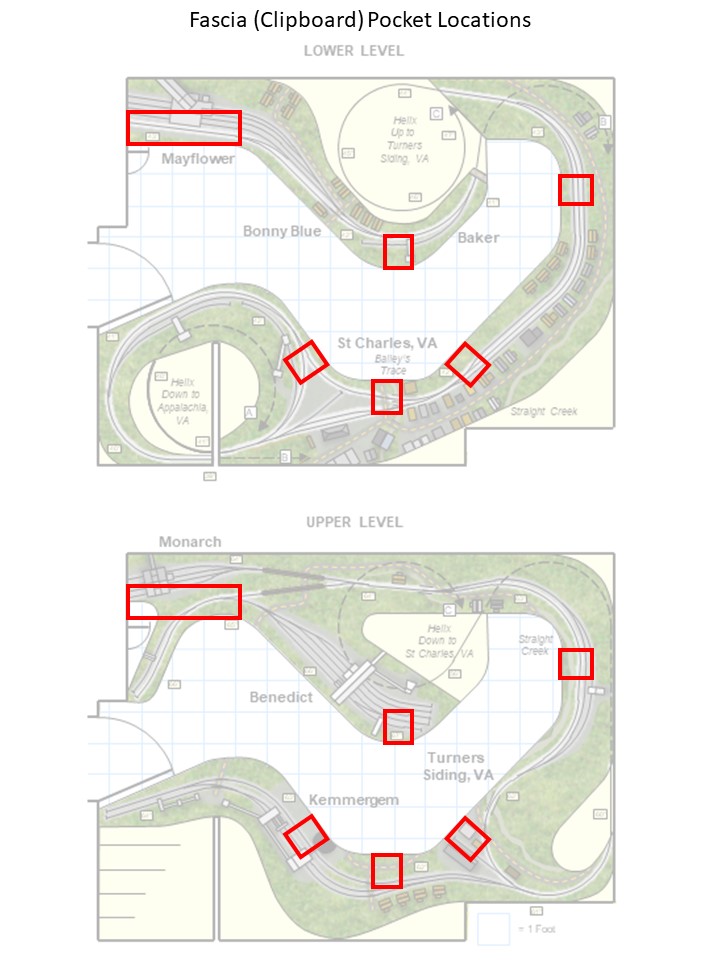

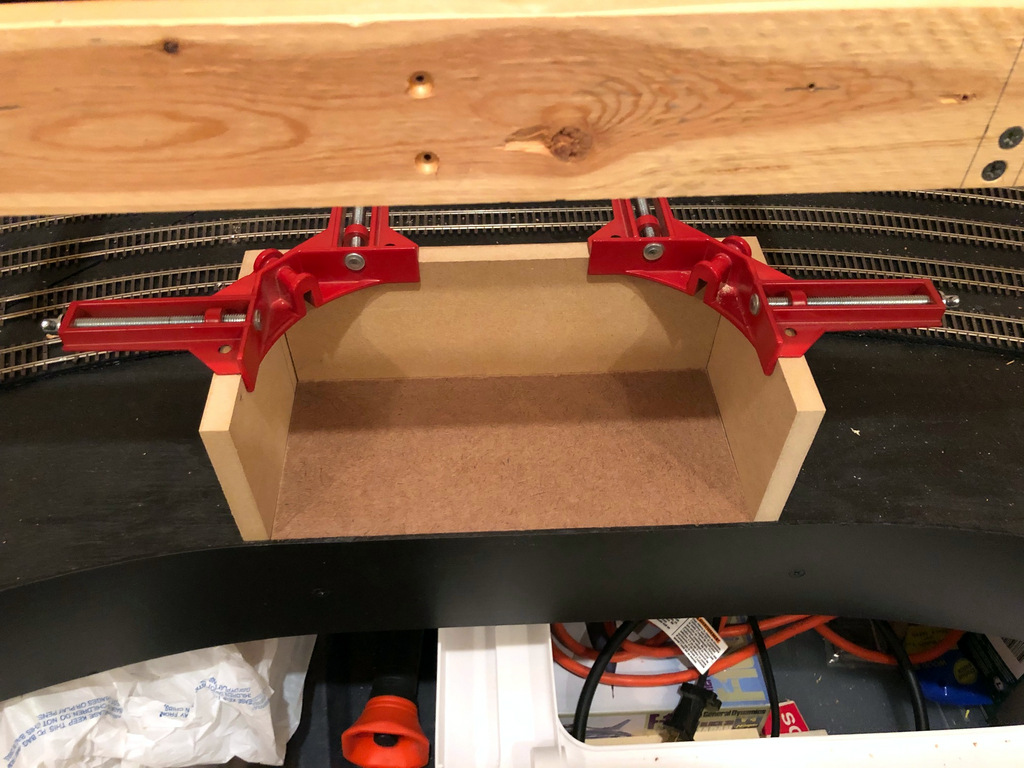

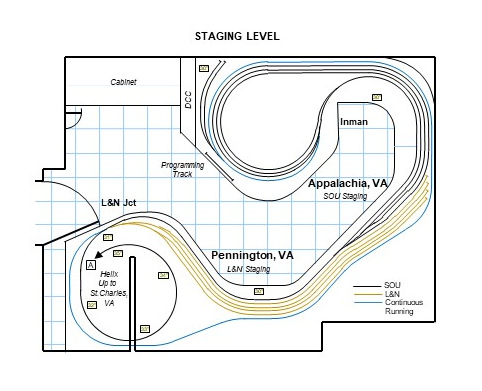

I’ve finally started laying subroadbed onto the main level of the layout, and I’ve chosen the section between Baker and Mayflower as my first scene (see track plan). Mayflower is the first of four large tipples on the layout, so to make sure I’ve got proportions and track spacing right in the plan, I decided to build an HO scale mock-up from foam core and cardboard first. I’ll just warn you, this is not a time-saving process, but it certainly helps you visualize a scene and make adjustments before building more permanent structures and track. Because this was the first and the only large tipple on the lower deck where vertical spacing would be important, I decided it was worth the effort.

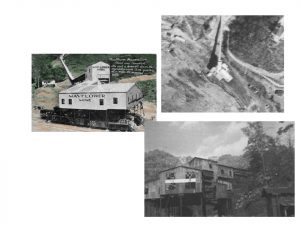

Step 1 – Research. I’ve made a commitment to modeling the tipples as closely as possible (rule: no Walthers New River Mine allowed–it’s not a bad kit; it’s just over-used and too recognizable). The trouble is this area is not well documented by photos, so there’s a lot of guesswork and extrapolation involved. The first resource I had was a track chart that showed four tracks under the tipple, a medium-sized operation. Next, I found an aerial photo from the 1960s that showed the basic footprint of the tipple and the distinctive portion of the tipple connecting the tipple to the mine that sits 45 degrees to the tracks. Finally, I found a single grainy photo of the front of the tipple and a painting of it from a post card that someone had posted to Pinterest. With these resources, I had enough to rough-out a drawing.

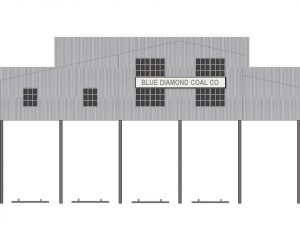

Step 2 – “Scale” Drawing. Regardless of whether or not I’m building a mock-up or the final model, I need some sort of scale drawing to build from, and for tipples that were one-of-a-kind, actual drawings are very rare. I use the word “scale” here loosely because none of the research offered any clear dimensions. Still, distances between tracks and height above hoppers can be estimated, so I did my best. To make the drawing, I used my favorite drawing program, MS PowerPoint. No, PowerPoint isn’t designed for this, but it’s easy to use, and you can draw lines to specific dimensions and angles. I would work on one side, matching it as best I could to the photos. Then I’d copy relevant bits from the one side to use as size references for the next side until all the parts were drawn. Some sides were longer than a piece of paper, so I drew these as two separate drawings I could glue together later. The tricky part was the photo and postcard showed two different time periods for the tipple. The photo showed a section added to the front over two tracks, so I had to figure out how this might have worked in concert with the tipple represented in the postcard.

I decided to draw windows and corrugated metal siding on it as well. This was a simple matter of making a generic window and copy/paste it in place. The siding was just a texture I found online and copied into scale sheets to place behind the drawing (use the “send to back” function on right click). When everything looked decent, I printed it out.

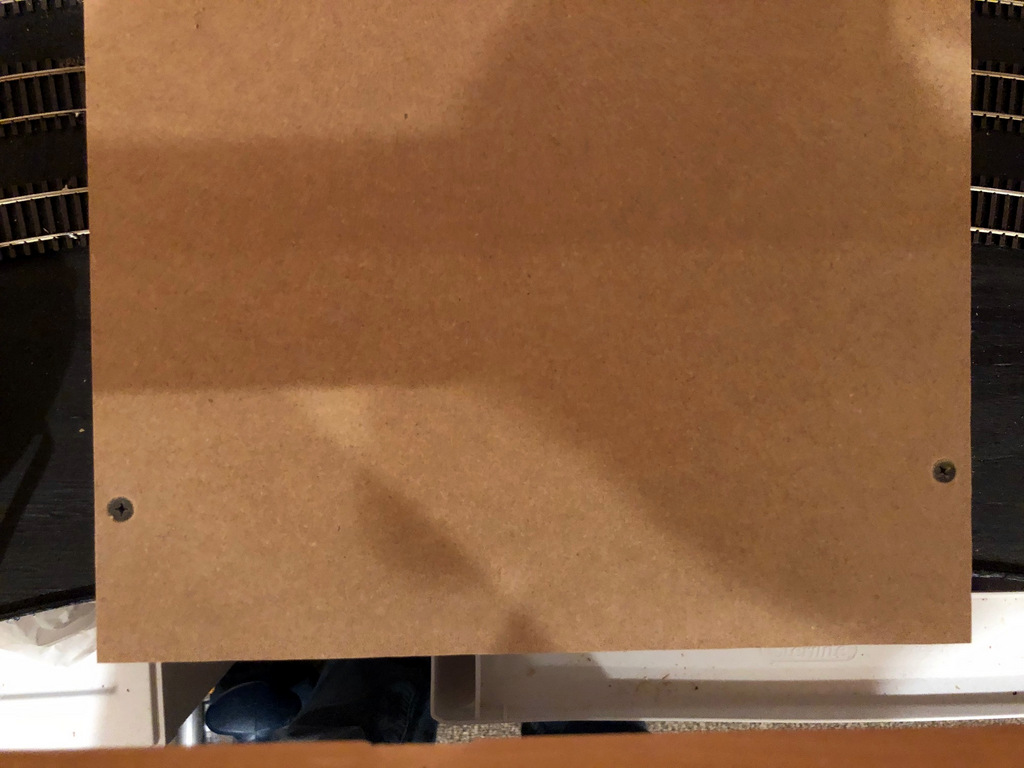

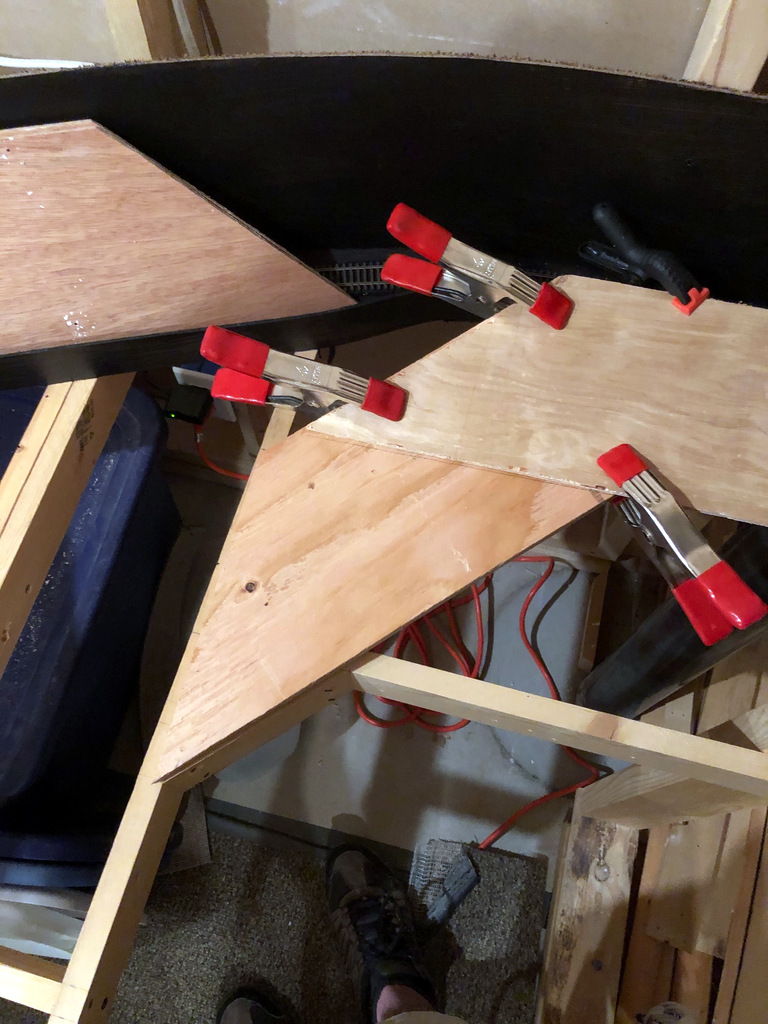

Step 3 – Building the Mock-Up. For material, I used black-on-black 1/4″ foam core picked up at the local big box hobby store. It’s easy to cut and work with and has enough rigidity to make a durable structure. I cut out pieces of the drawing and then glued them to the foam core using normal white glue. Where I have a corner, I needed to pick one wall to recess the width of the foam core so they won’t overlap (i.e., when gluing the drawing would overhang the foam core by one foam core width). As you can see from pictures, the glue caused a little discoloration and warping of the paper, but hey, it’s a mock-up. Next I cut along the edges using a metal ruler and X-Acto blade. The trickest part by far was cutting the intricate frames of the leg pieces (5 total). A mock-up doesn’t really require this level of detail, but I decided it was important enough to judging the look of the tipple that I spent an extra 3 hours or so cutting these out. The glue and paper caused some of the sides to bow a little, so for these I cut out 1/2″ wide strips of foam core to attach perpendicular along the back and bring them back into shape and provide lateral strength. This required laying a heavy book on top while it dried, but it worked well.

With the pieces cut out and strengthened, I started gluing them together. I worked on one corner at a time and used little pieces of square foam core to keep the corners square. I added structural pieces of foam core wherever needed to keep things sturdy. Again, the trick was to work one joint at a time (no more than two) instead of trying to build it all at once. The glue dried sufficiently in about 30 min, so I’d just come by every 30-60 min and glue another side on. Finally, I made the roof out of corrugated cardboard salvaged from a box–it’s a little thinner than the foam core but still has sufficient rigidity. After test fitting the roof pieces and making adjustments with the blade, I glued on the roof pieces–this is tricky because you have to worry about a lot of edges at once.

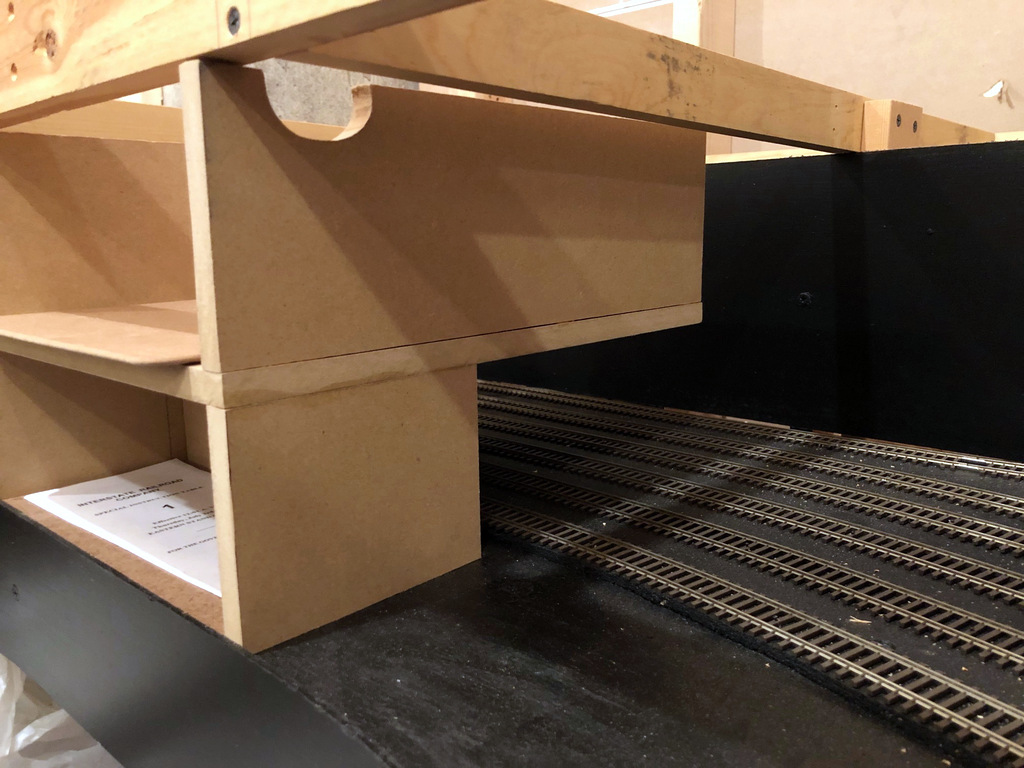

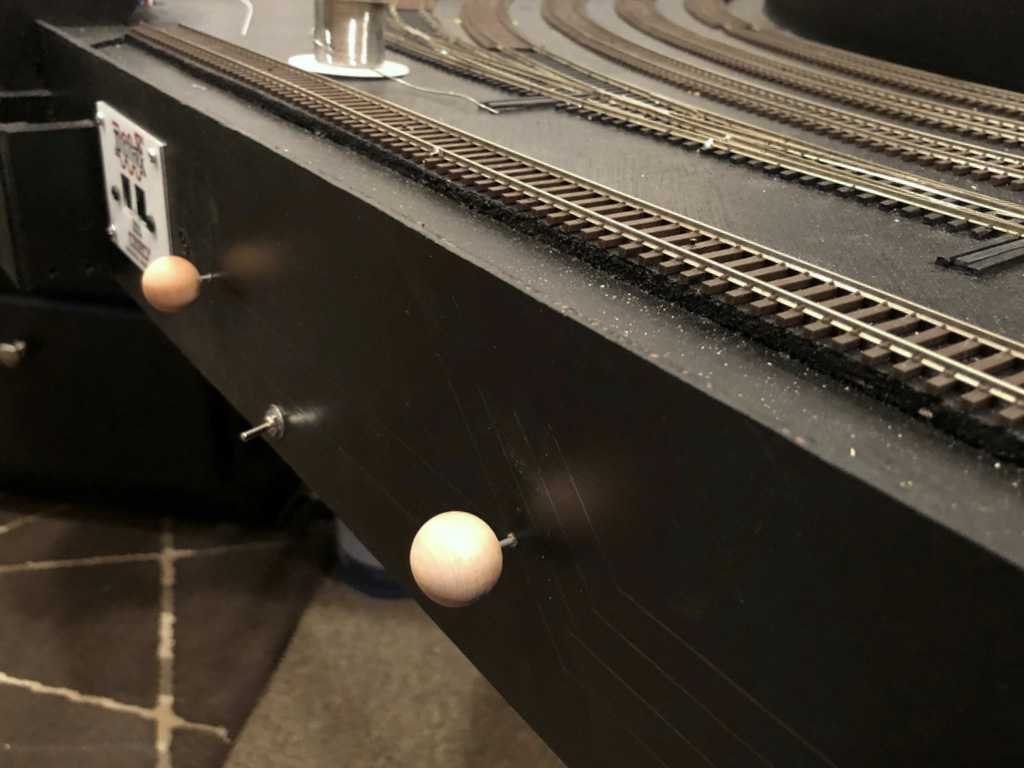

Step 4 – Evaluating the Scene. With the Mayflower Tipple mock-up complete, I could now mock-up the scene on the layout and see where the tracks would go, how tight the spacing would be for hoppers (adequate), how far I could bring it out or push it back in the scene, how much space I would have with the upper deck, etc. As it turns out, the tipple fits perfectly and doesn’t need any adjustment, but it would be easy to make cuts and repairs to the mock-up to try different things that would be a lot tougher to do on a final model. Any changes would simply be added to the drawing to use for the final model.

Conclusion. While I could have been halfway done with a permanent model in the time I built this mock-up, I now have the confidence in my drawing and in the scene to build the final model. Besides, it will be a while before construction on the upper deck in this area will be complete enough to install a permanent model, so in the meantime, the mock-up will give me and other crew members a good stand-in to enhance operations that I don’t mind getting a little roughed up. Beats having to use your imagination when switching out empty and loaded hoppers!