First, beware someone with 6 months of experience offering you advice… ok, if you’re still reading, I like your sense of adventure! I steered clear of sound decoders for years because I knew as soon as I started, I would need to upgrade the whole fleet to be happy, and it was going to be a huge investment in money and time. Other than a one-time fling with a Digitrax Soundbug many years ago, I really dipped my toe in the water when I picked up a couple of locomotives sound equipped from the factory a few years back, an Athearn GP38-2 with Soundtraxx Tsunami and an Atlas C420 with ESU LokSound v4. I tried installing one cheap drop-in sound decoder in an Athearn/MDC RS3, and that was not a positive experience, so I stopped for a while. Finally in February, I decided it was time to figure this out, so I did a bit of research and dove in! Here are a few things I’ve learned in the first 6 months and 12 sound decoder installs.

It’s not as tough as it looks. Not gonna lie, I’m the adventurous kind of person who doesn’t mind taking a hacksaw to a $200 locomotive, but I was SUPER intimidated by installing sound! What I found is once you’ve got a few basics down, it’s only a little more difficult than installing a standard decoder (which isn’t that difficult). The toughest part is finding a good space inside the locomotive to mount the speaker(s) while still leaving room for the decoder and other vitals. I’ve only destroyed one sound decoder in the process (more on that later), and I have gone back and redone some of my first installs based on lessons learned over time–extra time but no biggie.

You get what you pay for. Big surprise, this maxim applies to sound decoders too! I tried to go cheap at first and found a “great deal” on a one-piece drop-in decoder for an Athearn RS3. It even came with a speaker on-board–what a deal! Installation was very easy, but to me it sounded like a screeching lemur with its tail caught in a coffee grinder… the horn was tolerable, but the rest of the sounds were painfully inadequate and unconvincing. I tried building a baffle around the thin piece of plastic acting as the speaker, but it only improved the bass performance slightly with no improvement to the actual sounds. In the end, it was a waste of money and time, and that decoder spent most of its short life with the sound switched to “off.” If you love the screeching lemur decoders, I’ve got two more I’ll sell you cheap!

Following that experience but still wanting to save a LITTLE money, I tried out the “Econami” decoders from Soundtraxx. These were about twice as much as the screeching lemur decoder but still only 2/3 the price of a full-fledged sound decoder, so it seemed like a good place to start. The Econami was lightyears ahead of the screeching lemur in terms of sound quality (same basic sound quality as the Tsunami 2 series), and it had all the features I thought I wanted. After I equipped a few locomotives with Econamis, I splurged on my first Tsunami 2, mainly because the Econami didn’t have the EMD 567 turbo sound I needed for a GP30. Once I played with the “extra features” I didn’t think I cared about, I found that those features were worth the extra cost, at least in my “lead” locomotives. So what’s the difference? First, I’m very happy with my Econamis and would still highly recommend them for “in the consist” locomotives that use the prime movers available on the decoder (Alco 244, EMD 567 non-turbo, EMD 645 turbo, EMD 710 turbo, GE FDL-16). The prime mover sounds are, indeed, the same as the sounds on the Tsunami 2s. However, the Tsunami 2s have more noticeable depth and variety to the secondary sounds like valves, compressors, radio chatter and even toilet flushes. The biggest difference I’ve found is how the sounds correspond to the throttle and loads if you take the time and effort to really configure them which I’ll talk about later.

Sound decoders are tough, but you can destroy them. I’ve found sound decoders to be tougher than they look, but they’re far from indestructible. They’re designed with either wires or soldering points that make them easy to connect to your locomotive, and I haven’t destroyed one with a soldering iron yet. However, sound decoders pack a LOT onto a little board, so the individual components can be small and fragile. I found this out with an Econami decoder I installed (poorly) in an Athearn RS3. I got everything to almost fit, but I needed just another millimeter of clearance, so I pressed the decoder down. Well, because of my poor choice of installation location, it forced a metal protrusion of the frame into one of the board’s components, and that was that! No more blue light, no more sound, no more movement, lots of heat where there shouldn’t have been… toast. So, be gentle with them, and don’t do anything to make direct contact with the frame or to put pressure on any single component. Expensive mistake but valuable lesson!

Take your time arranging the components in the install. The one decoder I fried was a victim of poor component placement in the locomotive. Usually the decoder sits above the motor like any other decoder, but it doesn’t have to–I’ve placed the decoder in the cab of a couple of RS3s because there just wasn’t room above the motor. The tougher trick is finding a good spot for the speaker(s). Most locomotives currently in production will leave a good spot for this, but many of my locomotives were purchased well before sound was much of a thing. I’ve crammed speakers in the long hood, the short hood, in the cab, on top of the decoder, you name it! A couple of times on some old Proto units (they filled every last inch of those shells with weight), I’ve had to take a hacksaw to the weight and carve out a piece of real-estate in the nose. I find that mounting the speakers to the frame assembly is more convenient and practical than mounting them inside the shell, but you can do either. Just make sure the speaker is sitting on something reasonably solid like a piece of the frame, or in some cases, a thick plank of styrene cut to go across the top of a truck. For attaching the speakers, I like to use 3M double-sided foam tape because it holds well while still enabling a little movement from the speaker so it doesn’t rattle its mount. The 3M tape is tough to remove if you want to change things, though, so I know others have sworn by servo tape.

Sound installations require a LOT of wires, so I’m careful not to make the wires too long, and I use liberal amounts of shrink tubing and electrical tape to keep the wires from making a rat’s nest inside the shell. I’ve found my wiring has gotten a lot neater over the course of a dozen installations, so expect a little trial-and-error here.

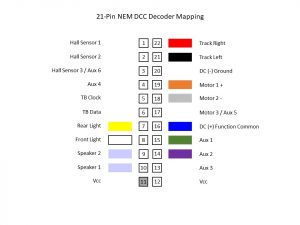

You can, indeed, hardwire a 21-pin decoder without a harness (but it ain’t fun or recommended). One of the downsides of the Soundtraxx Econami is it’s only offered in two sizes, the larger “plug-n-play” (ECO-PNP) board and the much smaller 21-pin version (ECO-21PNEM). The PNP is a drop fit for many locomotives, especially locomotives from the previous generation of factory DCC or “DCC ready” units. But it is kind-of long. The 21-pin is about 1/2 the footprint, so it’s the perfect size for smaller HO-scale locomotives where the PNP won’t fit, but… surprise, it needs a 21-pin harness which is only found in newer locomotives. I tried to buy a 21-pin harness, but they’re expensive enough that it effectively makes the Econami install the same price as a similarly sized, full-featured Tsunami 2 TSU-2200 series decoder. Hmm… could I hard-wire the 21-pin decoder? Turns out the answer is “yes,” but it’s definitely “off label” use that will probably void your warranty, and I would only do it in dire circumstances. For me, “dire” happened to be the cramped quarters of an old Proto 2000 GP7 and an Athearn/MDC RS3 (once I removed the screeching lemur). There are two tricks to this process: 1) know which pins do what. This was surprisingly difficult to figure out, and I ended up translating a diagram from German (the translated diagram is included for you here). 2) use solid wire that fits firmly into the socket to connect the wires. I bent the pin wire in an “L” shape, soldered it to the locomotive wires, and covered the wire-attached half of the “L” with a piece of small shrink tubing to keep it insulated from other nearby wires. This has worked great in 3 installs and has held up to >3 months of use! But again, not ideal… do this at your own risk.

When in doubt, try 2 sugar cube speakers (and call me in the morning… no wait, don’t call). There are some real sound artists out there who have a lot of intelligent things to say about speakers… I am not one of them. If I had to boil down everything I read about speakers into 2 things it would be: 1) use the biggest speaker you can fit, and 2) use a baffle (the housing that goes behind a speaker). First-generation locomotive speakers were variations of the traditional paper cone design, but more recently, smart phones have ushered in a revolution in small speaker technology, and we benefit from tiny but impressive speakers nicknamed “sugar cube” speakers. Two sugar cube speakers take up about the same room as a traditional oval cone speaker, but a pair seem to provide clearer sound and slightly more bass, so I’ve settled on a pair of sugar cubes as my basic, minimum speaker requirement in most locomotives. I use the LokSound sugar cubes because they come with a nifty little baffle kit that includes options for a shallow or deep baffle and options to mount one or two speakers to the base. If they’ll fit, I like to pair the sugar cubes with the deep baffles on a single base, but the shallow baffles sound almost as good if you don’t have the room for the deeper sides. I’ve seen some 3D printed baffles to go with sugar cubes as well, and I’ll definitely be giving these a try soon.

Impedance mismatching is a thing, but it isn’t the end of the world. Impedance, a form of resistance, is measured in ohms like a resistor. Those real sound artists of whom I am not one have written a lot of great articles on impedance and why it’s good to match the impedance of the decoder to the impedance of the speaker. I can’t explain it, so I’ll take them at their word! A typical sound decoder impedance is around 8 ohms (like the Soundtraxx units I use) as are many speakers, including the sugar cubes. But wait, I remember from somewhere that if you run two identical resistors in series or parallel you change their resistance by either double (series) or half (parallel). No worries! unless you’re running your decoder at max volume, this is not likely to be an issue. For example, LokSound recommends using speakers between 4 and 32 ohms, so there is a range. Just stay safe in the 1/2 to 2x range and don’t get too crazy. For reference, I wire my 2 sugar cubes in series.

When it comes to volume, less is more. Speaking of volume, I’ve found that on a layout with multiple sound locomotives, less is more on the sound volume. I usually set my master volume around 10-20% of the max output. I like to hear it in my ear at the volume I would expect to hear it if I were standing at the same vantage point (about 150 scale feet away) as an HO-scale person. I also take the time to tweak the levels of individual sounds to avoid letting any one locomotive dominate the room and to focus on the main sounds like the prime mover, horn, and bell. I keep the horn and bell pretty muted, though, as not everyone in the train room needs to know every time a train comes to a crossing. I set them just loud enough to be heard clearly over the prime mover by the crew initiating the horn or bell (to everyone else it’s an annoying distraction from their train).

Also, listen to the engine for a while and see what secondary sounds you like and don’t like and adjust them. For me, the poppet valves of the Econami decoders sound very loud and sharp and express themselves a bit too often, so I set the decoder to make these sounds more quiet and less frequent. On the full-featured Tsunami 2s, there are a myriad of secondary sounds. Most add well to the symphony, but I didn’t appreciate all of them. For example, the sound of a socket wrench is not something I’m used to hearing when train watching, so I turned the volume on this “extra” to zero for most of my locomotives. Other sounds like the radio chatter, doors opening, and toilet flushes I turned down so they’re barely audible. Again, I want the prime mover to shine and the background sounds to be in the background.

Configure each locomotive a little differently. Speaking of the extra sounds, decoders will come from the factory with a default setting for volumes and frequencies of sound. If you don’t tweak these, you may end up with decoders with “random sounds” being synchronized with other locomotives… not very realistic. I make sure each locomotive has a slightly different rate for sounds that can be rate-configured to avoid this and make the sound of each locomotive slightly unique.

JMRI Decoder Pro makes programming sooooo much easier. Decoder programming is all about configuration variables (CVs), and sound decoders have a LOT of things to configure! Soundtraxx uses a ton of CVs (like 500 for their Tsunami 2). LokSound has fewer CVs, but each CV can be used to configure multiple options by adding together the numbers associated with the options you want and entering the sum into the CV (it’s math, but at least it’s pretty simple math). You can skip a ton of this math and programming CV by CV by using JMRI’s Decoder Pro–it’s seriously awesome, and I never appreciated it more than when programming sound decoders! It turns programming into a set of selections on conveniently grouped tabs and uses plain language descriptions of variables instead of CV numbers. This is particularly helpful with Soundtraxx programming because each CV only controls one or two options, so its easy to separate them. It’s a little more complicated with LokSound because the decoders are “blank” and the sounds loaded separately after manufacture, usually by a dealer. They’re loaded as a “sound project” into the decoders “slots.” While there are some conventions on what sounds go into what slots, it’s really up to the person who designs and loads the sounds, so instead of sounds being conveniently labeled as “prime mover volume” and “horn” in Decoder Pro, you have to work with labels like “slot 1” and “slot 2”–still easier than manually programming each CV. JMRI and Decoder Pro are free software, and all you need is some kind of computer/DCC interface which most DCC systems offer. While you can use it with a stand alone programming track, I’ve found “programming on the main” to be a much better option for sound because you can hear every change in real-time.

Put the most used functions in F0-F6. Most newer decoders, including the Soundtraxx and LokSound decoders, allow you to “remap” the functions from the normal DCC convention to wherever they’re needed. Sound wasn’t a common thing when DCC conventions were set, so it’s not surprising that the conventions may not allow for convenient access to sounds. Also, the number of buttons on a throttle is limited, so you want to make sure the ones easiest to access (single push) are the ones you need most often. DCC is amazing, and I’m so grateful for those who made it happen for the hobby–they were brilliant! However, there is one unconscionable omission in DCC that I do not understand: braking. All decoders allow the programming of acceleration and deceleration (momentum), but some have no braking function so there’s no way to slow the locomotive down except to “e-stop” (ouch) or wait for the momentum to bleed off. The combination of momentum and a sound decoder is AWESOME, so I knew I wanted this and a way to easily control braking via the throttle. The sound decoders I’ve played with all have braking options, but the braking is implemented differently in each decoder. With enough tweaking, I was able program braking that feels right into both the Soundraxx decoders (Econami and Tsunami 2… not so much on the Tsunami in the Athearn GP38-2) and LokSound decoder. While sounds like couplers are cool, I decided easy access to a “brake” button was more important, so I had to remap my functions. As I use Digitrax UT4 throttles, all the important functions needed to be programmed into F0-F6, the only “one push” functions on the UT4. Here’s how I mapped them:

- F0 – Headlight on/off (standard)

- F1 – Bell (standard)

- F2 – Horn (standard)

- F3 – Short horn (standard on Soundtraxx)

- F4 – Dynamic brakes (sound only, no braking action)

- F5 – Light effects (gyralight if equipped, dimming if not)

- F6 – Brake (complete with a nice stop-sign sticker on my throttles)

You need to play around to really make them sing. To get the most realistic sound out of a decoder, you need to really play around with it and make lots of tweaks (there’s a reason there are so many CVs). On a real locomotive, the sound is not tied to speed as much as load and demand. For the economy decoders like the Econamis, you get what you get, and the prime mover pitch is tied to the throttle setting. You can use function buttons to increase and lower the RPM sound, but who wants to have to control their throttle AND RPMs separately? Some might, not me. What you REALLY want is for the decoder to sense the load and other factors and change the pitch according to the load. The key to this is the decoder’s use of Back EMF (BEMF) which essentially allows the decoder to sense the load on the motor. With the LokSound decoders, the use of BEMF to control the prime mover sound appears to be native in the decoder’s function. For the Tsunami 2s, it took a bit more work to configure this, but it is SOOOO worth it! Soundtraxx calls this “Dynamic Digital Exhaust” (DDE), and it requires the tweaking of a few CVs, two to tell the decoder your idea of “low speed” and “moderate speed,” one to control the prime mover based on the difference between your throttle setting and current speed (this is where building in some accel/decel really helps), and one to tell it how sensitive to be to the BEMF.

By 1) adding in a good bit of momentum, 2) turning up the “speed differential” CV to full blast and 3)upping the BEMF sensitivity to about 30% of max, I get a locomotive that sounds very realistic to my ear. When I move it from idle, I crank the throttle up immediately to where I want the speed to be. The prime mover howls to life with a roar because it senses a difference in its current speed (zero) and the desired speed. The locomotive, still belching sound, then begins to creep slowly up to speed, and the prime mover quiets a lower level as the actual speed closes on the desired speed. After that, the BEMF helps it know if it’s under load or not, so it’ll drop back to near idle going downhill, and it will notch up if moving uphill, especially if its moving a lot of cars uphill with it–perfect!

Another tweak I highly recommend is the dynamic brake setting which can be done even on some of the economy decoders. For most model applications, you don’t actually want the application of dynamics to slow the train. You’re going to control the train speed with the throttle, and the “dynamics” are just ear candy as they’re presumably helping you keep the speed in check going down a grade. Soundtraxx has a CV you can select that will drop the engine sound to idle if the dynamic brakes are applied. I like this because when I’m heading down a grade with a loaded train, a single function button push allows me to drop the prime mover sounds to idle and bring up the dynamic brake whine while still moving the train at a realistic speed. Cool!

Speed matching is really important for the cool features. I’ve always been a “close enough” guy for DCC locomotive speed matching. This has served me just fine until now. I was so excited when I figured out how to use DDE to make my locomotives sound amazing in response to throttle inputs and loads, and then I put two of these amazing locomotives together in a consist. When just the the two of them were creeping along together downhill and their prime movers were screaming at “notch 8,” I knew something was wrong. Turns out, if locomotives aren’t perfectly speed matched, one is always pushing or shoving on the other. The BEMF in the decoder translates this as “load” and adjusts the sound accordingly which means notch 8 sounds for notch 1 action. I spent hours painstakingly speed matching locomotives to a single locomotive I picked as the “pacer” using 28-step tables and trim for each locomotive. This was time well spent as multiple locomotives sound far more realistic now that they’re not fighting each other.

Advanced consisting is a big help. Before sound, I used Digitrax’ “universal” (command-station) consisting almost exclusively. Now that I have sound-equipped locomotives, I’ve switched to “advanced consisting” (decoder-aided consisting). Advanced consisting has a couple really useful features. First, you can configure the locomotives on the ends of the consist to only use their headlights when the consist is moving in a particular direction–this is crucial for my layout where switching is common and the consist changes directions all the time. Also, you can configure most functions in any locomotive to respond to either the consist address or only the locomotive address. This allows you to pick a single locomotive in the consist to respond to horn and bell functions–I wish this could be configured to respond based on direction as well (the lead locomotive’s horn and bell are used and switch based on direction), but alas, this doesn’t seem to be a feature yet. Most importantly for sound, this allows me to program functions like dynamics and braking to respond to the consist address in ALL locomotives so they work as a team in both sound and braking.

Once you pick a manufacturer, stick with them. I’m not here to tell you which manufacturer to pick, but I will say, its a lot easier if you pick a manufacturer and stick with them! I heard this advice from others, and I now wholeheartedly agree! It’s far easier to make your fleet act in concert, especially when M.U.’d, if things like momentum and braking are implemented the same in all the decoders. While it may sound appealing to have a smorgasbord because you like one manufacturer’s Alco sound and another’s first-gen EMD sounds, it will limit your ability to implement consistent features and “feel” across the fleet. Having said this, I still use (and love) the one LokSound-equipped C420 I have even though everything else is Soundtraxx. Thankfully, the L&N train it powers is usually run by a single locomotive, so I just had to tweak it to feel and act more like the Soundtraxx equipped locos, but it doesn’t need to be a perfect match because it’s never M.U.’d.

Every manufacturer has their pluses and minuses, so pick the features that work for your operations (aka “why I picked Soundtraxx”). You really can’t go wrong with the leading manufacturers, and you’ll find zealots and haters for each. They all do things differently, though, so ultimately you have to figure out what your priorities are. I hear great things about TCS WowSound, but I have no personal experience to share. I wanted to jump in, so I evaluated the LokSound and Soundtraxx locomotives I had on hand to see which I wanted to use on the fleet. When just listening to the sound, especially as it changed based on how I was operating the locomotive, I prefered the LokSound. However, when I began playing around with things like braking and tweaking CVs, I found the Soundtraxx was far more intuitive to configure, and now that I know how to use DDE in the Soundtraxx decoders, I’m able to get a lot of the same sound dynamics out of my Tsunami 2s that seem to be pre-programmed in the LokSound. I can live with complicated programming, so what it really came down to for me was one simple thing: Soundtraxx has a reasonably featured “economy” line that works for many of my locomotives. Interestingly, as I’ve gained experience, I’m still happy with the Econamis, but I will probably invest in full-fledged models from here on out because their extra features enhance my enjoyment enough to justify the extra cost. The Econamis will still have a home in B-units, mid-consist units, and units that only see service occasionally.

If you’ve stuck with this article to this point, good for you for listening to a rookie! I hope some of my learning points will help you as you make decisions and jump into the world of sound decoders. While I won’t encourage a battle of which manufacturer is best, I would encourage those of you with experience in this area to add some of your own lessons in the comments. If you’ve learned nothing else from this, I’ve hoped you’ve at least learned that it’s not a good idea to use a sound decoder that sounds like a screeching lemur.