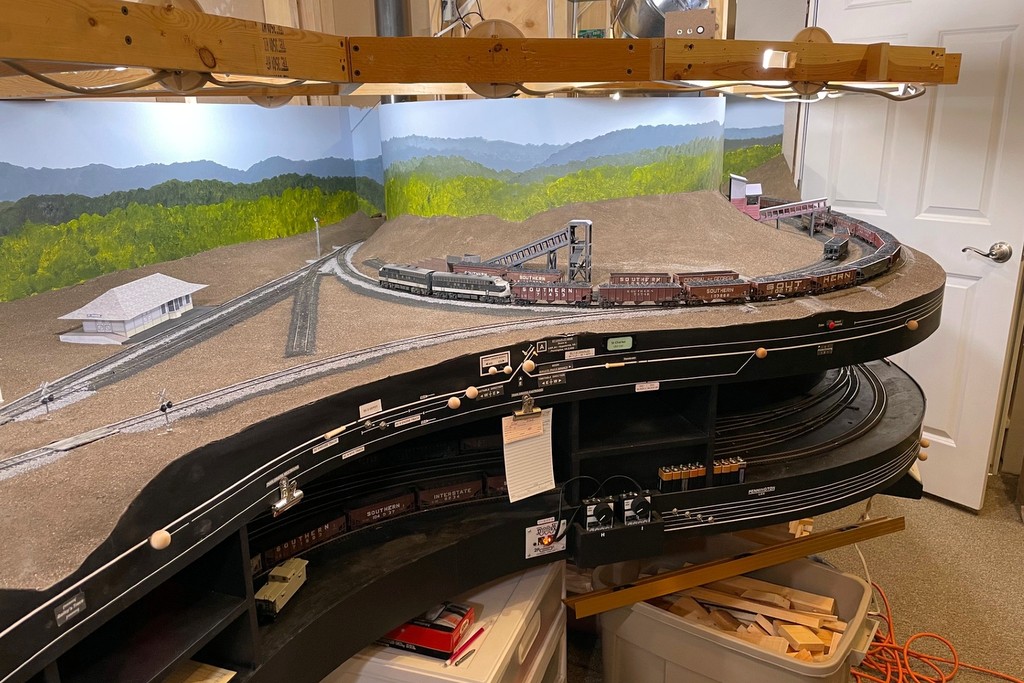

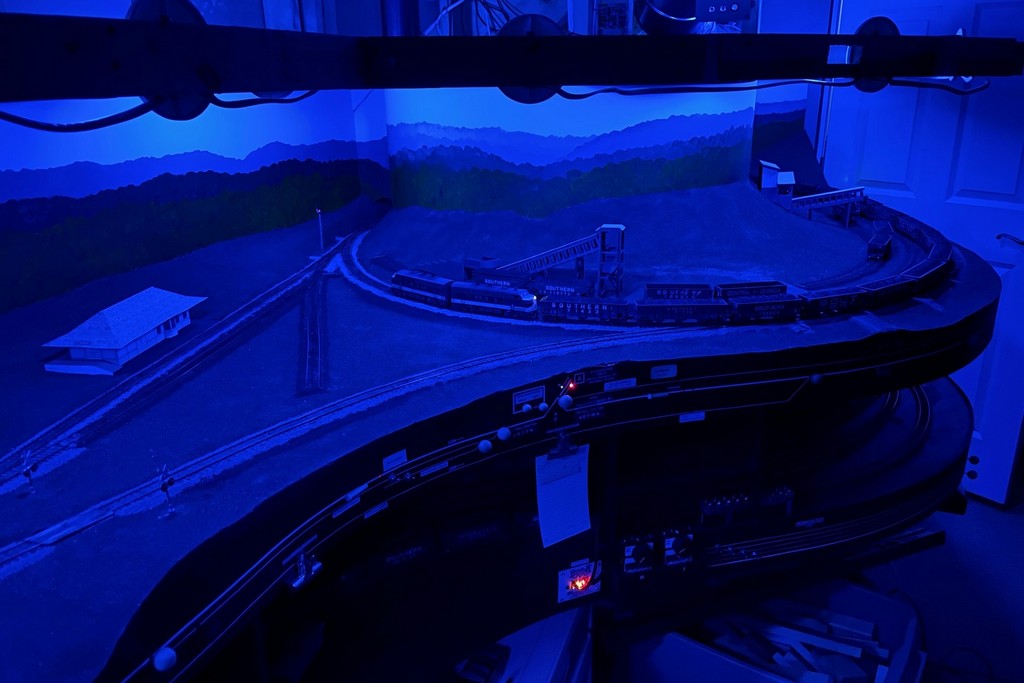

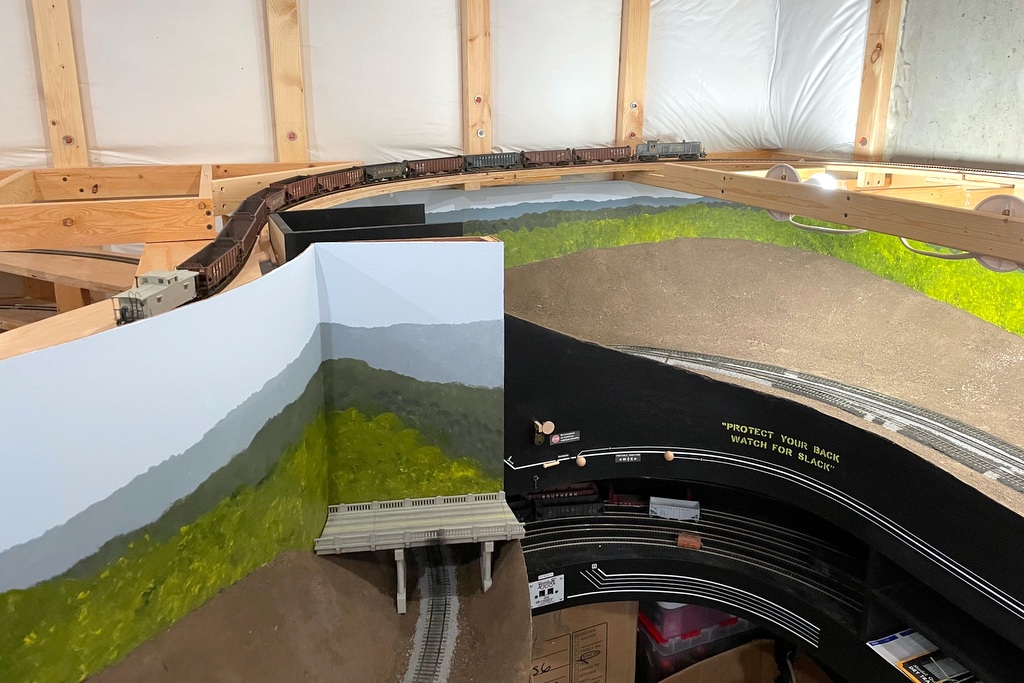

With a portion of the upper-deck benchwork in place, I was able to complete the connector track from the top of the helix to the top of the grade along the back of the layout. The moment of truth had arrived where I would figure out if a key assumption I had made would hold true. My helix is aggressive: 24″ radius and 3% grade! At the top of the helix is an S-curve into another 24″ curve in the opposite direction and a short straight section to reach the top of the grade. Based on experience with the first helix (also 24″ radius and 3% grade), I estimated my lightest engine could pull about a dozen empty hopper cars and a caboose up the helix. The lightest engine is an Athearn RS3 used on the CV Local, and in the 1960s and early ’70s, this job only hauled a handful of cars onto the St. Charles Branch, perhaps 6-10 on a given day.

I loaded up an RS3 with 12 cars (including 3 really heavy Tangent cars) and headed for the first helix. With the Tangent cars, the RS3 stalled out on the grade–uh oh! I removed one hopper and tried again. Thankfully it was able to climb the first hill, albeit with the throttle at 1/4 speed and the Tsunami2 howling at run 8! After a brief respite of relatively level track in St. Charles, the train attacked the second helix to the upper deck. Three-and-a-half turns and 20″ higher, the train exited the helix and entered the S-curve, coming to the crest of the grade without stalling. So, 11 cars is my current limit, and while it’s slightly less margin than I had hoped, it’s good enough that it won’t restrict my operating scheme.

Just to be sure, I latched a pair of Intermountain F7s to 33 Southern hoppers and tried the same thing. No problem! Two locomotives have plenty of power to haul more than enough cars up the grade. It was cool to see trains actually running on the upper deck, even if the section they’re currently in will be hidden by hills.